In a world where memory is often institutionalized and tucked away in remote repositories, T-Kay Sangwand is pioneering a different approach—one that centers communities in the preservation of their own histories. As a librarian for the UCLA Digital Library Program, Sangwand works to make digital archival collections accessible while ensuring that marginalized voices retain control over their narratives. But her passion for community-based archives stretches far beyond the digital stacks.

Sangwand’s journey into archival work began with a profound commitment to social justice. “As an undergrad, I majored in Gender Studies and Latin American Studies, focusing on social movements,” she says. “It was working at Scripps College’s Denison Library that inspired me to pursue an MLIS. I thought I’d take a more traditional librarian role, but an archives course with Dr. Anne Gilliland showed me the power of archives in community memory work, and I was hooked.”

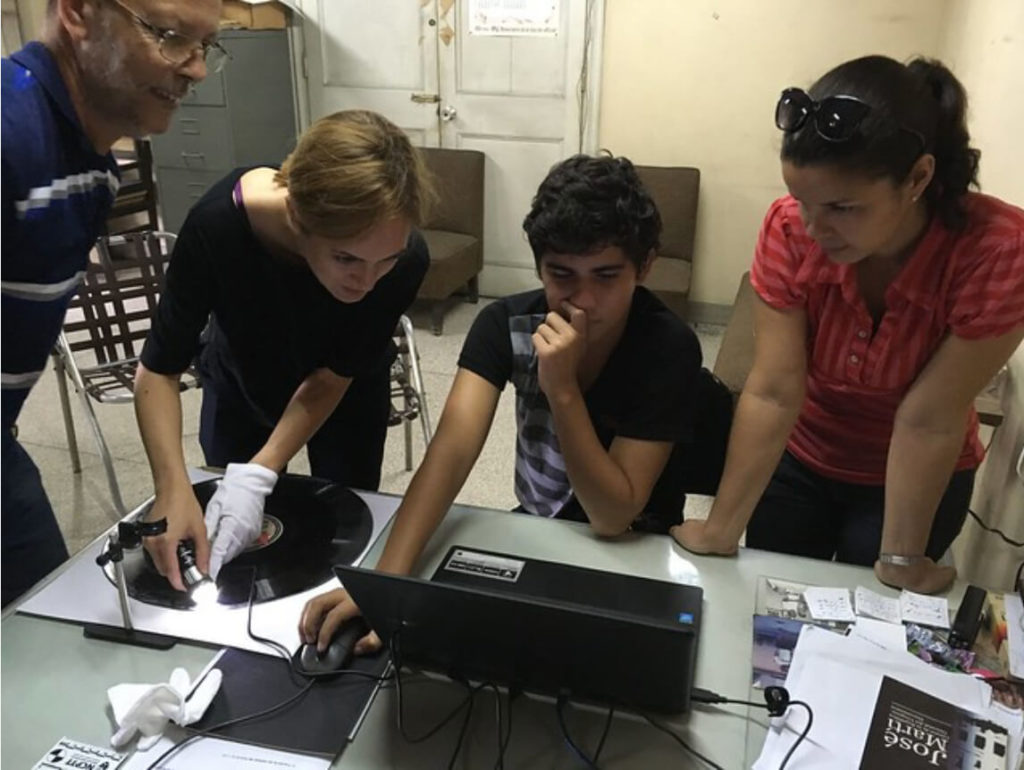

Her trajectory has been anything but conventional. Before landing at UCLA, Sangwand served as the Human Rights Archivist at the University of Texas at Austin, where she led post-custodial archival collaborations in the U.S., Latin America, Africa, and Asia. These initiatives aimed to ensure that communities maintained intellectual control over their archives—a hallmark of Sangwand’s ethos.

Redefining Archives: Community-Driven Memory Work

In the world of archives, traditional practices often involve relocating physical collections to a designated repository where they’re maintained by professional archivists. While effective for long-term preservation, this process can strip communities of their agency. Sangwand’s work flips this model on its head by placing the power back into the hands of those whose histories are being preserved.

“Community-driven archives are typically guided by the principle that the people whose histories are documented will be the ones to steward those archives,” she explains. “This is particularly important for marginalized or underrepresented groups, whose histories are often erased or misrepresented.”

Instead of being passive subjects, community members become active participants, retaining control over how their stories are told and shared. “In post-custodial collaborations, larger institutions provide support, but the community-based partners maintain intellectual control. They decide how materials are described, in what language, and how they’re accessed,” Sangwand adds.

A Cultural Legacy in Xochimilco

Perhaps one of her most inspiring projects was as a Fulbright Scholar in Mexico City, where she worked with youth from Xochimilco to document the diverse traditions of Día de Muertos across the region. This UNESCO World Heritage site is known for its unique blend of pre-Hispanic and Catholic rituals, making it a rich cultural hub.

“Two youth leaders, Carlos Mendoza and Víctor Bastida, spearheaded the project,” says Sangwand. “They gathered 83 people, including students and community members, to document Día de Muertos practices across Xochimilco’s 14 native communities and 17 neighborhoods.” Sangwand provided the archival framework, structuring the digital archive and designing workflows for accession and description.

The challenges were immense—especially managing contributions from 70 people, many of whom had no prior experience with digital archiving. But the rewards were even greater. “The community support was overwhelming. Numerous people opened their homes to be interviewed and documented,” Sangwand shares. The project resulted in two books, La fiesta de los muertos en Xochimilco and Los que suben ¿ya no bajan?, and fostered a deeper connection between the people of Xochimilco and their cultural heritage.

Ethical Archiving: A Delicate Balance

One of the central tensions in community-driven archives is ensuring that the voices of the community are authentically preserved without crossing into appropriation or extractivism. Sangwand is acutely aware of this challenge. “Archives and archivists that don’t originate from the communities whose histories they aim to preserve are never entitled to those histories,” she cautions. Her work is built on trust, collaboration, and a deep respect for the community’s ownership of its stories.

Sangwand emphasizes the importance of building reciprocal relationships. “GLAMS professionals must ask themselves if they are willing to advocate for community partners in ways that do not solely serve their own institutions. Building trust takes time—sometimes years—and it requires asking hard questions about motives and long-term commitments.”

The Future of Community-Driven Archives

As community-based archives grow, Sangwand predicts that they will become increasingly independent from larger institutions. This is a significant shift for GLAMS professionals, who have long relied on partnerships with community-based projects. “Community archives are becoming more financially stable and gaining expertise, making them less reliant on universities or large institutions,” she observes. “If GLAMS institutions want to remain relevant, they need to reflect on their practices and move away from extractivism.”

As for Sangwand, her motivation remains deeply personal. “I remember visiting the Japanese American National Museum and silently crying in the gallery, overwhelmed by the power of seeing my family’s history valued and preserved. Everyone deserves that experience.”

In a world grappling with the erasure of marginalized histories, Sangwand’s work is a reminder that archives are not just places of preservation—they are spaces of empowerment and reclamation. For GLAMS professionals, her message is clear: to collaborate with communities is not to collect their histories, but to ensure they thrive under the stewardship of those who live them.