A recent Supreme Court ruling holds the potential to either champion the rights of artists, writers, and musicians, or potentially stifle creativity, subjecting arts and information organizations to copyright lawsuits. In September, the Open Copyright Education Advisory Network (OCEAN) convened a discussion centering on the case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, and the potential implications it may bear for libraries, archives, museums, and galleries.

Leading the discussion was Anne Young, director of legal affairs and intellectual property at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. The panel featured Kyle K. Courtney, copyright advisor at Harvard Library and Fellow at NYU Law’s Engelberg Center; Brandon Butler, director of information policy at University of Virginia Library, and Sriba Kwadjovie Quintana, intellectual property manager, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

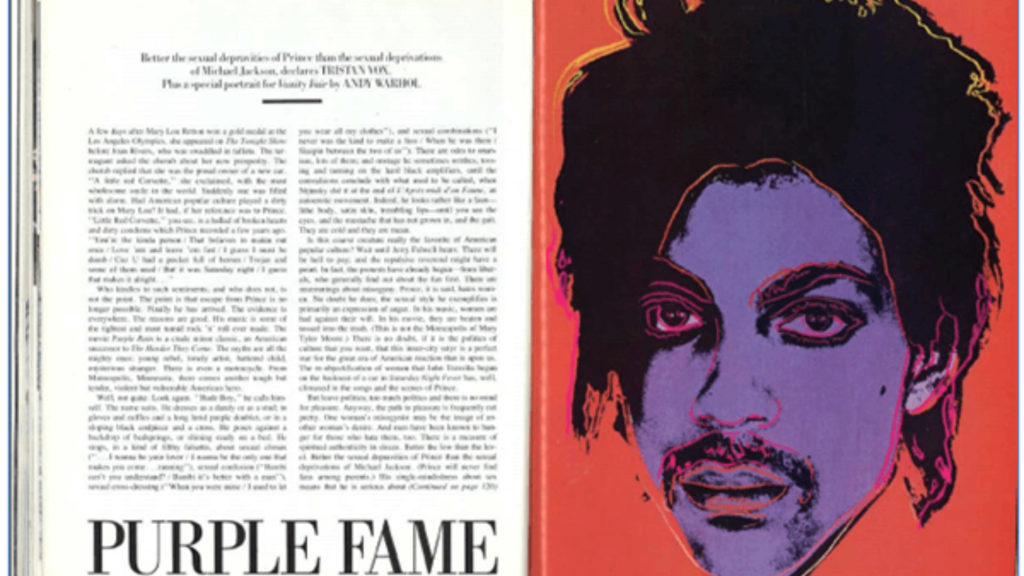

Kyle Courtney kicked off the conversation by providing a concise overview of the Warhol v. Goldsmith case dating back to 1981. This pivotal event revolved around Vanity Fair magazine’s payment to photographer Lynn Goldsmith for her photo of the musician Prince, with Andy Warhol simultaneously commissioned to create an article illustration based on the same photo. Subsequently, Warhol used the photo to create a series of silkscreen illustrations titled the “Prince Series,” a move unbeknownst to Goldsmith. Legal contention arose when Vanity Fair featured one of Warhol’s Prince series illustrations as their cover art after Prince’s passing in 2016, prompting a copyright violation lawsuit by Goldsmith. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Goldsmith (7-2 majority), asserting that Warhol’s illustrations did not constitute transformative fair use.

Fair use, a legal doctrine permitting the use of copyrighted works under specific circumstances, was scrutinized through Courtney’s distillation of its four evaluation factors:

The Court’s focus primarily rested on the first factor – the purpose and character of the use. The justices contended that Warhol’s portrait of Prince lacked sufficient distinctiveness and was used for similar purposes (as the cover of Vanity Fair), rendering it unprotected under fair use. Courtney emphasized that the Court’s attention was confined to the “specific challenged use” (the cover illustration) and did not extend to whether Warhol had the right to create the entire Prince series.

Courtney shared that Justice Elena Kagan and Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., wrote in their dissenting opinion that this decision would impede creativity across various domains, hindering the progress of art, music, literature, and the expression of new ideas and knowledge.

Brandon Butler, the director of information policy at the University of Virginia Library, addressed what the potential implications of this new Supreme Court ruling, following years of successful fair use cases, on libraries, archives, and museums. Before the Warhol decision, landmark fair use victories like Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust, Georgia State, and Apple Inc. v. Corellium had paved the way for these institutions in utilizing their collections. Butler asserted that while caution is warranted, organizations should persist in their current endeavors, recognizing that their role encompasses a distinct purpose that differs from mere substitution.

The discussion then shifted toward its impact on museum work. Sriba Kwadjovie Quintana, intellectual property manager at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, acknowledged the challenge of determining direct impact at this juncture. Nevertheless, she found significance in the Court’s acknowledgment of the right of the Warhol Prince series to exist, without expressing an opinion on its creation, display, or sale. This left pertinent questions for museums concerning artists’ creative processes, use of copyrighted materials, and implications for promotional marketing materials and store products. Quintana urged museums to exercise vigilance in licensing of reproductions and merchandise, and emphasized the importance of reviewing their collections for works with possible underlying rights, especially those featuring featured individuals, notably celebrities.

Quintana also encouraged museums to deliberate on their artist commissions and acquisitions. While museums should not assume the role of fair use arbitrators, it’s imperative that legal agreements ensure artists are cognizant that their work does not infringe on the rights of others.

The sessions concluded with a lively question and answer session involving artists, librarians, and museum professionals. Topics ranged from amendment rights to whether this ruling signifies an impediment to creative expression, as well as the significance of effective contract drafting.

The upcoming OCEAN session, “Preservation, Research, and Learning With Video Games,” is scheduled for Dec. 1. Details regarding registration and other forthcoming sessions can be accessed on the OCEAN website.

Council on Library and Information Resources

1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600

Alexandria, VA 22314

contact@dev.clir.org

CLIR is an independent, nonprofit organization that forges strategies to enhance research, teaching, and learning environments in collaboration with libraries, cultural institutions, and communities of higher learning.

Unless otherwise indicated, content on this site is available for re-use under CC BY-SA 4.0 License